|

Colin Chapman’s long-held wish to build and

enter one of his cars in Grand Prix racing finally came to be with the

Lotus 12, the beginning of the line of open-wheelers that eventually won

seven F-1 constructors championships.

In 1956 the FIA announced a new Formula 2 regulation to be enacted the

following year. In the UK

it was decided to begin racing immediately under the new rules with cars

already in existence, most of those being Lotus Elevens.

But Chapman quickly drew up a new single-seat design and had a

Lotus 12 prototype on display at the London Motor Show in October.

The prototype was meant strictly for show, with a wooden

transaxle, a frame with hardly any weld-metal, just enough room for a

non-functional Climax FPF, and highly cambered deDion rear suspension.

Woe to anyone who copied this much-photographed

and very defective example!

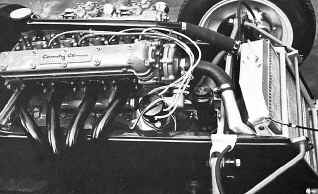

Viewed from the side, the frame of the 12 had clear relationship to the

Eleven, but with a more sharply raked seatback angle and inverted

triangulation to the cockpit. The

plan view was of an exceptionally narrow car: the frame barely wide

enough for the engine and the driver’s shoulders. In all a tiny package, with the driver sandwiched between the

Climax FPF and a rear-mounted transmission.

It was expected that 150 h.p. could be harnessed in just 620 lbs.

of race car. Chapman’s

philosophy of economical use of space and mass was at, or beyond, its

practical limits.

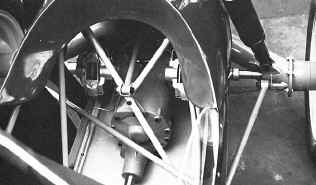

At the front the prototype had an innovation that had been on

Chapman’s mind for months: a

new twin- wishbone suspension here made its debut, replacing the infamous

Lotus swing-axle. The new

suspension incorporated an anti-roll bar that played double-duty as the

forward half of the top wishbone. This

setup became a mainstay of various Lotus cars for many years.

The 12 also introduced the ‘wobble web’ alloy wheel, another

of Chapman’s initiatives, but made to work by designer ‘Mac’

McIntosh. However,

many features of the prototype were not seen again, as production models

were improved with better chassis and Chapman’s first use of

strut-type suspension at the rear.

The 12 was largely unsuccessful as an F2 or an F-1 machine although in

the hands of Cliff Allison it had some fine moments and nearly won at

Spa in the ’58 GP. But it

and the later type 16 also helped give Lotus a reputation for

fragile and unreliable performance.

While performing in high-visibility events was Chapman’s dream,

failures in front of those audiences were hard for everyone to

forget.

What the 12 did for the Eleven was to force some attention onto ways the

Eleven could be improved for more horsepower and higher speeds.

It preceded the Eleven Series 2 by several months and lent some

of these innovations – with more successful results – to the

sports-racer.

Readers wishing to learn more about the prototype Lotus 12 should locate

issues #40 & #41 of Historic Lotus, with very interesting articles

by Mike Bennett and David Morgan. |