|

The Lotus Eleven that rolled out for the motoring press

debut early in

February 1956 was different from all

the other cars that followed. It was different enough to cause years of

confusion and debate among Lotus researchers. The photographers gathered

that day at Alexandra Palace in London included Louis Klemantaski, and each

had ample opportunity to capture the car from every angle and get

close-ups of every detail. It was fortunate that they examined it so

well because three months later it was probably shunted beyond

recognition, and the ensuing rebuild changed the features that made it

unique. This essay is about the short life and significance of what has since been

called: the Press Car.

For February 10th 1956, the cover of AutoSport

announced the new Lotus Eleven to the

world. Other automotive weekly magazines, Autocar

and the Motor also ran articles describing the car,

each quoting the same specifications, and to some extent the same

phrases that probably came from Colin Chapman himself. This Lotus Eleven

was painted, while others at the Lotus shop at Hornsey would be sent to

their new owners in raw aluminum. But many more important details of

this car differed from all subsequent models. The single-skin doors,

inner front fenders attached to the frame instead of the bonnet,

unfinished dash panel and missing headlamp covers all indicate a rushed assembly as well as its prototype status mentioned in the texts.

But there was an engineering oddity visible in the photos: a unique rear

suspension layout that differed from the description given in the

articles.

announced the new Lotus Eleven to the

world. Other automotive weekly magazines, Autocar

and the Motor also ran articles describing the car,

each quoting the same specifications, and to some extent the same

phrases that probably came from Colin Chapman himself. This Lotus Eleven

was painted, while others at the Lotus shop at Hornsey would be sent to

their new owners in raw aluminum. But many more important details of

this car differed from all subsequent models. The single-skin doors,

inner front fenders attached to the frame instead of the bonnet,

unfinished dash panel and missing headlamp covers all indicate a rushed assembly as well as its prototype status mentioned in the texts.

But there was an engineering oddity visible in the photos: a unique rear

suspension layout that differed from the description given in the

articles.

Each of the weeklies described the rear suspension as having been

developed from the Mk 9. Each described twin parallel radius arms used to locate the

deDion tube front to rear, with lateral location made with a short diagonal

brace angled to give the effect of a much longer Panhard rod.

But the photos in the Autosport story show a single radius

arm on each side and a strange, full-width, curved arm attached to the

sides of the chassis and the center of the DeDion tube. There was no

explanation for the discrepancy.

Each of the weeklies described the rear suspension as having been

developed from the Mk 9. Each described twin parallel radius arms used to locate the

deDion tube front to rear, with lateral location made with a short diagonal

brace angled to give the effect of a much longer Panhard rod.

But the photos in the Autosport story show a single radius

arm on each side and a strange, full-width, curved arm attached to the

sides of the chassis and the center of the DeDion tube. There was no

explanation for the discrepancy.

Another early article about the Eleven had an interesting revelation. MOTOR

RACING, in  its March 1956 issue, featured the Press

Car (with Chapman driving) on its cover and a full page of details

inside. As Graham Capel once noted, “Motor Racing was

a monthly publication, unlike the previous weeklies and could not get

into print as quickly with hot news.” But consider that Motor

Racing may have also been given a look at the car in advance of the

other magazines, in view of its delayed publication. Its photos

weren’t taken at Alexandra Palace but at Hornsey. Instead of a garden

setting we see canvas tarps as background and what was undoubtedly the

inside of the recently constructed assembly building for the Eleven. Motor

Racing had two different photos of the rear suspension arrangement,

and this is where they had an exclusive. (For a

reprint of this article, click the 'cover' at left.)

its March 1956 issue, featured the Press

Car (with Chapman driving) on its cover and a full page of details

inside. As Graham Capel once noted, “Motor Racing was

a monthly publication, unlike the previous weeklies and could not get

into print as quickly with hot news.” But consider that Motor

Racing may have also been given a look at the car in advance of the

other magazines, in view of its delayed publication. Its photos

weren’t taken at Alexandra Palace but at Hornsey. Instead of a garden

setting we see canvas tarps as background and what was undoubtedly the

inside of the recently constructed assembly building for the Eleven. Motor

Racing had two different photos of the rear suspension arrangement,

and this is where they had an exclusive. (For a

reprint of this article, click the 'cover' at left.)

The text of the article notes that: The deDion tube is located by

three tubular radius arms, two of which are parallel fore and aft but

the third forms a semi-circle at the rear of the chassis. Colin Chapman

has had second thoughts about this as will be seen in the captions to

the photographs. The caption of the first deDion photo, showing the

curved arm, states: The curved prototype locating arm, just visible,

will be superceded by a method illustrated on page 77.

Then, on the second photo we see: Finalised DeDion layout for

the Lotus Mk XI. . . . And this is the 'conventional' layout the

other magazines described, but seen only on a bare chassis.

Perhaps the reporter had more of an opportunity to enquire about the curved

arm than the others did at the press gathering, or that Chapman needed to explain why a different design was also in the shop.

This was a stage in development where each Eleven being built had

something unique in its chassis or suspension, and comparisons were

being made. Three of the first cars would soon be put on a ship for the

USA, to give the car its race debut at the Sebring 12 hour, and to bring

some needed sales and cashflow. Another would be sold as a kit for Jabby

Crombac to build. Through February and March production would be at full

speed to get the Eleven program moving in the UK, and it was imperative

that the design be finalized. The mention of “second thoughts” about

the suspension in early February suggests that Chapman had already

tested this car against another.

The first batch of production chassis, as many as ten, had

provision for mounting the curved locating arm in reinforced holes at

the sides of the seatback bulkhead. But they also had brackets for

mounting the straight upper and lower radius arms. Perhaps the Press

Car lacked the necessary brackets needed to equip it like the others

and, as it was already paneled, welding in the brackets wasn't

practical. Something, perhaps

the desire to do more testing, prevented it from being 'standardized.' It took four decades for the outside world to know

it, but this was the only Lotus Eleven ever equipped with the curved

locating rod.

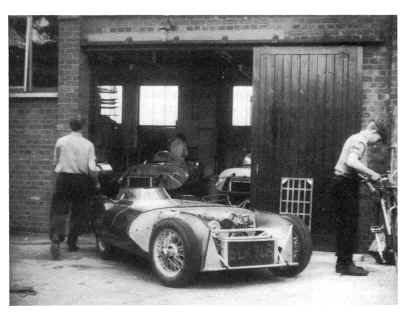

We get another good glimpse of the Press Car in Jabby Crombac’s

biography, Colin  Chapman. On page 65 we see it emerging

from the shop, with Chapman rushing around. The bonnet is off and we

have a clear view of its unique prototype inner fenders. Three siblings

are in the background of the photo, still undergoing assembly, and a

bare chassis is on the floor. Barely

visible, a registration number SLK 7(?)8, is scrawled on the radiator.

This would be Mark Fitzalan-Howard’s car, who bought it,

registered as SLK 748, in April. Factory records show the second

Lotus Eleven being sold to Howard, and that was chassis no.151. Chapman. On page 65 we see it emerging

from the shop, with Chapman rushing around. The bonnet is off and we

have a clear view of its unique prototype inner fenders. Three siblings

are in the background of the photo, still undergoing assembly, and a

bare chassis is on the floor. Barely

visible, a registration number SLK 7(?)8, is scrawled on the radiator.

This would be Mark Fitzalan-Howard’s car, who bought it,

registered as SLK 748, in April. Factory records show the second

Lotus Eleven being sold to Howard, and that was chassis no.151.

Some have suggested that 151 was to have been Chapman’s personal car,

and this would have made it the 'works' car, with the often-used

registration 9 EHX. It's an interesting notion, in light of Chapman usually setting his own

car’s specification to a higher standard than the others he sold.

Perhaps, early on, the curved arm was thought to be an advantage worthy

of exclusive development. Some of the first cars to race in the UK,

notably those of Allison and Bicknell, had the normal rear suspension

arrangement, and they suffered from handling problems. Chapman is

supposed to have found a quick cure for this, and it was probably just a matter of not enough caster angle. But Chapman’s 9 EHX was also

reported to have had handling problems, and if it was chassis no.151, he

dealt with it by getting rid of the car.

Over the next thirty-five years speculation rambled on about what had

become of the Press Car, and where were the other early Elevens

with curved locating rods? It was thought that the car Chapman tried to

race at Sebring had one because of the large clearance scoop visible in the

undertray, clearly revealed when co-driver Len Bastrup rolled the car

in front of photographers. It

was also thought that the Press Car had been the first Eleven,

the prototype, and that upon finding a curved location rod in an Eleven

the discoverer could shout “eureka!” and claimed to have found it.

In all the international discussion no one ever seemed to suspect the

Fitzalan-Howard car, perhaps because it soon vanished from the record.

A first-hand account on the Fitzalan-Howard car finally came from Dave

Kelsey, founder of Progress Chassis and, as someone who built the

frames, who certainly knew his Elevens. Kelsey wrote the letter below to

the Historic Lotus Register late in 1992.

Some of his more

illuminating remarks are highlighted here.

“In the HLR magazine, you

raise the question of the ex-works Elevens. Well, one Climax car was

sold to Mark Fitzalan-Howard and Maurice Baring in bits, and Sid Marler

and I assembled it for them in Mark’s garage in Cadogan Mews, behind

his parents’ house in Eaton Place. I can’t remember why it was in

bits, but probably Chapman had removed anything useful before selling

it.

“On completion of the Eleven, Mark arranged for a test day at Goodwood

in company with the leather Connolly brothers and their father, and

Maurice Baring, and we trooped off in convoy - the Connollys’

Westminster, the Eleven driven by Mark, Maurice’s brand new Aston

DB2-4, and my Ford Thames van. I distinctly remember passing one

unsuspecting victim on both sides, with my van and the Lotus on the

grass on one side, and the Westminster and Aston on the other.

“I had to stop for petrol on the way, and when I arrived at Goodwood,

I drove to the track just in time to hear a howl and a shriek as Mark

stuffed the Eleven into the chicane on his first lap. He did very little

damage, and I straightened out the track rods and pulled away the

bodywork ready to go again. I was sitting in the car, engine running,

about to start my first lap when the Duke of Richmond, who owned the

circuit, appeared, and said “you aren’t planning to drive that, are

you?” The upshot was that he refused to let us use the full circuit,

but agreed to allow standing start quarter miles, until the car had been

back to the works for a check. (I don’t know who he thought would

check it, if not me.)

“Sid, Maurice, Mark, and the Connollys all thrashed the car up the

straight on timed sprints, and it became immediately apparent that Mark

and Maurice had very little idea of racing gear-changing, achieving

times in the 20 second range. Sid and I took full advantage of the A30

gearbox and simply snapped through the gears without lifting off,

getting down to 16 seconds or so. Having exhausted the possibilities of

sprinting, we adjourned to Maurice’s superb pad in Godalming for tea,

where I left my van, taking Maurice’s Aston back to Hornsey for Bill

Griffiths to perform some magic on the carbs.

“The next move was to book Brands Hatch for further testing, and

having done nothing more to the car than I did at Goodwood, Mark,

Maurice, Sid and I started lapping in turn, each doing about five laps

before handing over. Mark and Maurice had their own contest, and Sid and

I vied for fastest lap around the 60 second area. (On the short circuit,

I hasten to add.)

“The car had a de Dion

rear, with, I think, a Watts link and single radius arms, and I found it

an absolute pig to drive.

The discs locked up at a touch, and even a judicious application of oil,

as recommended by Colin (who was on the scene) failed to even them out.

The main problem arose on the straight, which then had a hump which

prevented any sight of Paddock Bend until you were almost on top of it. Unfortunately,

the Eleven had the most excruciating rear-end steering when you lifted

off after heavy acceleration, and I found it a struggle to keep it on

the road.

“There were two choices - lift off well before Paddock, so as to get

it sorted before committing to the corner, or press on with fingers

crossed and teeth gritted in the hope that you would still be on the

tarmac at the approach to the corner. The former meant that when you

reached Paddock, the car was not going fast enough to drift properly,

and you were in danger of going off on the inside of the bend, while the

latter required more changes of trousers than I had catered for.

“As five o’clock and closure of the circuit approached, I was in the

lead on lap times  with 59 seconds, and Sid was set for a final attempt.

He came out of Clearways for the last time, selected second gear instead

of top at 105 mph, lost it,

and shunted the only thing there was to hit on the straight, a

marshal’s bunker. Sid popped out through the cockpit opening like a

pip out of an orange, did about the same number of cartwheels as the

car, and came to rest with a broken pelvis and sundry bruises. The car

did not fare so well, only the hubcaps remaining in their original form. with 59 seconds, and Sid was set for a final attempt.

He came out of Clearways for the last time, selected second gear instead

of top at 105 mph, lost it,

and shunted the only thing there was to hit on the straight, a

marshal’s bunker. Sid popped out through the cockpit opening like a

pip out of an orange, did about the same number of cartwheels as the

car, and came to rest with a broken pelvis and sundry bruises. The car

did not fare so well, only the hubcaps remaining in their original form.

“Eventually, the car bodywork was repaired in rudimentary fashion by

Norman Burgess, in London Colney, and even more eventually, I rebuilt

the rest, taking the opportunity to replace the rear suspension

with a twin radius arm and Panhard rod set-up in the hope of making it

more stable.”

The crash photo suggests two things: that Sid Marler was lucky

to escape with his life, and that a rebuild of this car must have been

total. Combined with this letter it adds evidence that the

Fitzalan-Howard car, SLK 748, was the Press Car. Several other

photos of the wreckage show details that match unique details of the car

photographed at Alexandra’s Palace. The fact that Kelsey and others

reassembled and finished a car the factory had sold in bits may explain

any other details that don’t match. And tellingly, Kelsey’s

characterization of the suspension as having a “Watts link” must be from his recollection of a central mount to the

deDion tube, because nothing else in a typical Eleven would suggest

this.

In selling this car to Fitzalan-Howard, especially in kit or disassembled form,

Lotus could be suspected of trying to bury a mistake. (Or is this too

cynical?) Kelsey once told Victor Thomas of the HLR that he had

negotiated the deal on the car between Chapman and F-H in April. It says

something for this car to have been surplus and disassembled at a time when the

factory was rushing to fill orders. Fitzalan-Howard was

not known for being able to race, and even though he reappeared in the

rebuilt SLK 748 by June of ’57, he never seemed to have any luck with

it. That August the car was

wrecked again, this time by Maurice Baring. Early in 1958 Fitzalan-Howard

and Baring took delivery of a Series-2 Eleven, and their S-1, the Press

Car disappears. Perhaps it was never repaired from the last shunt.

To this day it still hasn’t been found.

If Kelsey was correct in his diagnosis of rear-steer, the layout of the

curved locating rod and single (as opposed to two on each side) trailing

arm suspension would appear to have allowed the hub assemblies to twist

or yaw as forces (ie. throttle) changed. Under racing conditions it would

take less than one degree of change in rear-toe to cause a wicked rear-steer effect.

We know that Chapman later devised a controlled rear-steer in his

Formula 1 suspensions, where the outside rear wheel would toe-in under

spring compression. This carefully calculated effect might have been an

outgrowth of the discovery of unintentional steer in the earlier design.

It is food for thought.

Typical of Chapman, who at times could be stubborn with his ideas, a similar

full-width

lower control link with single upper radius

arms appeared years later in the series 2 and 3 versions of the Seven.

Here a single A-frame, pivoted from the seatback sides, was

connected to the bottom center of the rear axle through a bracket.

However, this method of axle location also proved troublesome.

Early owners soon discovered that these axles had never been designed for the

the stresses introduced by this fitment so oil leaks and more serious

complications could arise. Welded reinforcements to the axle were

soon added. Granted, the live axle of the Seven must absorb torque forces

not shared with a deDion tube. But

one may suppose that if the sturdy, live axle casings of the

Seven can distort under loading, the lightweight deDion tube on the Press

Car had little chance of always keeping the wheels pointed straight.

In the solution used on all subsequent Lotus Elevens (and ironically

also the Seven S-1) the deDion is located with two radius arms on each

side, with one of them incorporating a single diagonal tube forming an

A-frame to secure the axle laterally.

The diagonal tube and radius arms all direct their lines of force

near to where the hub bearings reside, thereby sparing the deDion tube from the

twists and stress of a centrally mounted bracket load.

Still, cracking of the deDion tube was a common problem, and the

Eleven series-2 was improved with one of larger diameter for this

reason. Also, Vic Thomas has drawn attention to the S-2 hub casting

having two integral “ears” for attachment to the radius arms. After

proofreading this essay he noted, “The hub casting for the series 1

has a single top locating ear only, which is no doubt testimony to the

fact that Chapman ordered 300 castings based on his original design.

This is overcome in practice by welding a pickup point to the bottom

endpoints of the deDion tube itself, a fault rectified by the series 2

casting.”

Despite its problems, the Press Car was pretty to look at when

new and did its job in front of the cameras well enough to be remembered

by Lotus Eleven aficionados ever since.

Its flaws were turning points in the embryonic development of

Lotus’ first major success.

|