|

In the notes

about different types of windscreens used on the Lotus Eleven (Dark Ages

item # 15) mention is made of the single-seat cockpit configuration most

often associated with the car. This

single-seat cockpit is sometimes referred to as the “LeMans” body

configuration, usually a part of the LeMans package with disc brakes and

deDion rear suspension. It

is one of the most striking features of the Eleven and proved to be

very effective in any competition event in which it was permitted.

This was part of the Eleven’s

super-aerodynamic bodywork, drawn by Frank Costin, engineer for DeHavilland Aircraft and brother of Mike Costin, the unsung

hero of Lotus.

When Frank Costin began to adapt his aviation-inspired concepts to Lotus

racing car shapes, he took great pains to impart directional stability into

his designs. At the time racing cars were of course faster than road cars

but not necessarily better handling, with slippery tires and high drift

angles the norm. Safer

control of the car at high speeds became an obsession to him, at least

as important as creating a low-drag shape.

The pronounced tail fins on the Mark 8 & 9, for example, had

nothing to do with styling. Costin

simply felt that aerodynamic improvements to allow the car to travel

faster should also bring aerodynamic resistance to sidewinds, and help

the driver keep the car going where it was steered.

By late 1955 when the Eleven was being designed Costin again

incorporated a vertical stabilizer into the shape, although drag

reduction was now the main function. 1

This time the side fins had been reduced to mere trailing edges

of the wheel enclosures. But

there in the headrest was a tailfin more obvious than ever.

In keeping with the modular, street or race, nature of the Eleven

this “fin” could be removed. So

when the “Press Car” was unveiled in February 1956, body panels were

laid out on the ground. Potential

buyers couldn't miss: this

car could be driven with either the racy single-seat cockpit with its

dashing headfairing, or as an almost practical open two-seater with a low-profile

“boot.” The new rocketship for the road set many a young man’s

imagination afire.

In Dennis Ortenburger’s book on Costin, the single-seat bodywork is

called “ yet another pure aerodynamic shape to cover the driver. (Costin)

arrived at an elongated canopy and then sliced its top off half way back

to allow the driver to get in. What

remained in front of him and to the sides was perspex.

The aft section was formed in aluminum and although called a

headfairing it really wasn’t. In

Costin’s scheme the entire shape, windscreen and headrest, faired the

driver and tests showed that the air flow remained remarkably well

attached even above the actual opening.” 2

That pure shape is best illustrated with the “Monza” bodywork as

seen here.

Not every full-spec “LeMans” Eleven had the single-seat cockpit, and

some Elevens that did were not LeMans.

Many Elevens were delivered to their owners with full sets of

road and track screens and corresponding bodywork. The

factory called the single-seat addition a TOP KIT and it

was an option with the

purchase of any Eleven or body

chassis unit. There was a proviso of course: the center section and

passenger's door had to have a recess for the tonneau which would have

been hard to add afterwards -- plus the easy addition of Dzus fastener

clips. The aluminum headrest was only

attached to the tail section with Dzus fasteners, and so could be used

as needed. Whenever the

single-seat windscreen was removed in favor of a full-width ‘screen,

the headrest was usually removed too because it immediately became an

air brake without the forward half of Costin’s “canopy.”

Ironically, the single seat cockpit with headrest were never used on

the Elevens that raced at LeMans. In

that race a full width windscreen was required from 1956-on for cars

that were ostensibly “two-seaters.” The same was true in 1957 for

Sebring and wherever the Eleven raced under the rules of FIA appendix C.

Due to this regulations change, a higher percentage of Series-2

Elevens were delivered with the full width screen, and no headrest.

In American racing the single-seat configuration with headrest was far

more popular with buyers. Only

the SCCA requirement of a rollover bar caused a problem.

On the Eleven the easiest place to mount a rollbar was the rear

face of the seatback, with a reinforcement tube from the bar back

to the right-rear corner of the chassis.

This arrangement could be made to fit unseen under the headrest,

but aluminum had to be cut to make it work.

To open and close the tail section the headrest would first have

to be removed, revealing slots and holes in the upper bodywork to clear

the tubes. The example at left is

typical. A few clever

owners also modified the headrest so that the front face was removable,

to enable it to the clear the bar.

The factory solution may have been at the request of Jay Chamberlain,

and only for the American market.

Many years later Chamberlain recalled 3

that as so many buyers wanted the headrest, a request was made of the

factory to make it integral with the tail.

This is consistent with the factory announcement: In

view of the recent S.C.C.A. ruling, a crash roll bar will be fitted as

standard to the chassis and this is hidden inside the head fairing. In

order to supply this, of course, the head fairing must be part of the

tail and not removable. 4 In this setup the headrest was open into the rear compartment,

and so the entire tail could be opened or closed around a rollbar

without the need to cut anything. The

integral headfairing is rare enough in the USA, and almost impossible to

find elsewhere. In the photos

at left we may have some of the factory examples.

In any event, despite the

existance of a few integral headfairings, most Elevens continued to be

produced with the removable type.

This is a

good place to insert a photo of the factory rollbar and photos are all

we have of these today, as original examples were replaced as more stringent

standards went into effect.

Note that the rollbar on this early chassis is slanted back to allow clearance for the hinged

tail section, actually making it less effective in protecting the

driver.

The priority was clear. But Lotus may have made a change to the

frame design to better support the rollbar later (mid-1956)

by switching the seatback diagonal tube to the

driver's side. This

is speculation but it makes sense.

A few homemade

headrests found their way onto Elevens too, such as the one on Dave

Tallaksen's ex-Sebring car. The

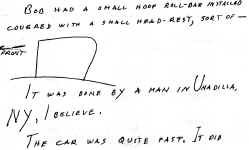

sketch at lower left is one eyewitness' recollection of the unique addition to Bob

Bucher's Club model, raced in the Northeast USA in the early 60s. (Does anyone have more on the Bucher Eleven? )

Lotus shrank

the headfairings on later models, as on the 15, with minimal effect on

vertical stabilization and more on simply shaping the airstream around

the driver. Only a few 17s had headfairings, and the mid-engined

19, 23 and 30 had none, relying entirely on the windscreen to shape the

airflow. It had already been observed with the Eleven that stability was good with or without the headfairing. As

for shielding the driver, Lotus had shown with the '57 LeMans Elevens

that it could be done with careful shaping of the 'screen and a higher

seatback line. The headfairings on those cars seems less prominent

as a result. Those special cars for LeMans mark the last time

Frank Costin was involved with the shape of the Eleven.

1 At

this point, Grahame Walter's influence in the earliest stage of the

body shape and design should be mentioned. Walter had done wind

tunnel tests on scale models that showed the efficiency gained from

use of a headfairing. In 1955 Chapman invited Walter to the meeting where Frank Costin first drew the Eleven's shape. The

incorporation of a headfairing in the design was one of Walter's

suggestions. Chapman was especially excited with the idea

of a headfairing option and the profits from offering

additional bodywork. Similar headfairings had been seen on other

cars already, such as the Panhard 750cc speed record car as well as

the Jaguar D-type.

2

Flying on Four Wheels, Frank Costin and his car designs –

page 57

3

In response to a question from Russ Hoenig at the 11th

annual Lotus Owners Gathering (LOG 11) in 1991, held at Waterbury,

CT. USA.

4 From Sales Bulletin #1, June 1956 from Colin Bennett to all overseas

sales agents. |