The First Lotus GT |

|

|

LOTUS MK 11 SPORT XJH 875 CHASSIS NO. 203 |

|

|

by Gilbert “Mac” McIntosh

|

|

|

|

These

are a few notes on the background of the car I built for myself and used

for several years as a road car. The

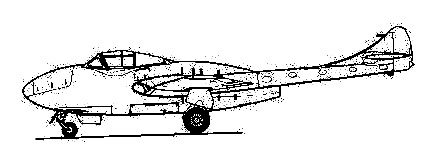

design of all the cars from the Mk 8 to the Elite was based on aircraft

practice rather than the very ‘hit and miss’ practice of the sports

car world. I was horrified by

the complete lack of data on loading cores for the structure so a lot of

the time on the 8 and 9 was spent working back from failures to what must

have been the applied loads. By

the time of the 11 we could design off the drawing board and get a light

structure which didn’t fail from fatigue or from an acceptable degree of

bump. It

was in this environment that the Elite idea first started:

we wanted a bread and butter money raiser to back up the Grand Prix

and sports racing cars. The

problem was how to make a G.T. car down to a price – a poor man’s

Porsche. A paneled space

frame was the Italian approach and we could do that, but the price would

be too great, as would the pressed steel chassis body unit – the returns

would be too small to pay off expensive dies. We looked at buying Ford 100E body shells, which we could buy

cheap, then fit our own suspension and engines – the route Lotus went

with the Lotus Cortina. The breakthrough came when Colin saw the little Bond sports car with a fibreglass chassis body unit at the Motor Show. He was full of it and we really kicked the idea round. The idea of a fibreglass chassis body unit answered all the problems on paper but there was a hell of a lot to do before we could design a car. I was OK on the structural side as far as stressed fibreglass mouldings went because I had used it on Vampire nightfighter radomes – mark you there were different types of mouldings to the car body mould – bathtub mouldings we called them. It may sound rude but tubs and most car fibreglass was 50% bulk filler with polyester resin and chopped strand mat whereas on the radomes and Elite [doors] we used satin weave cloth and epoxy heat cured resin. Most fibreglass structures would collapse into powder if you hit them with a hammer whilst on ours it just bounced back. I

had to get round the problem of an odd shaped box with a lot of cutouts

and no stress calculation background from the car world, they did it all

by eye and testing in those days. I

was used to aircraft stressing where every problem is different, so that

could be solved with a bit of basic stressing, but I saw another problem

where there was a lack of knowledge, rather as we were with the stressing

cores on the 8. That

problem was water-proofing because nobody would tolerate getting wet as

you did in an open sports racer, it used to come in everywhere!

It may seem simple “you just use sealant,” but I had

lived with the problem of sealing the integral wing tanks on the [DeHavilland]

Comet. It took DH years of

test work before we knew how to keep kerosene inside a bolted aluminium

wing without leaks on a production basis, and I could see a similar

problem on any new civilized car. Colin

could see the point but didn’t want the hassle at the works so the plan

was hatched that I would make my own civilized 11 Sports so we could learn

the drill. Where water flies

around under a car is not generally known so we had to do our own homework

– it took 6 months hard work before we got there. My

car had the standard Sports layout with a live back axle, 3 speed standard

gearbox and Ford 100E side valve engine.

Exhaust was normal multi-tube and twin SU carbs were fitted, but no

other tuning was done as it was to be a road car – replacing my 1928

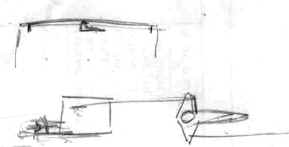

Austin 7 Chummy! At first I

used the standard full width F.I.A. screen but a hard top was on the way

as shown in the works brochure. I

can’t remember where the screen came from.

I certainly didn’t buy it or make it so it must have come from

Lotus but the top was all my design and manufacture and worked very well.

The top had a ˝” square 20 SWG mild steel perimeter frame with a

20 SWG aluminium skin riveted to it.

I can’t remember exactly how the rear lower window support went

other than that it fixed to the rear bodywork with a few bolts and

incorporated the pivot brackets for the hood.

There were two spigots on the top of the windscreen to locate the

front of the hood. These

spigots stuck into holes in brackets at the ends of the front tube and

locking was by a handle in the center and two rods to the locks at the

spigot housings. Again I

can’t remember the details other than that it was very simple and that

the handle was a [DH] Venom canopy release lever from the night fighter

test fuselage. I

know it may seem odd that I forget the details but you have to remember

that it was a long time ago and I was up to my ears in the design and

stressing of the new car, not to mention that this was only a hobby.

My real interest was aircraft design and I had a fairly large chunk

of the new 600 mph airliner on my drawing board.

We were right at the sharp end of the new jet airliner development

and life was very interesting technically.

Colin and I couldn’t understand people’s interest in past

designs other than as a source of data to make the next step on the new

cars – sad for the historians but fact! Back

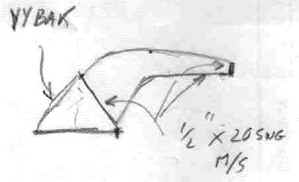

to the hood after that digression! The new window was Vybak, a flexible,

transparent, plastic sheet about 0.8 mm thick and it fastened to the rear

edge of the hood and the frame bolted to the body.

The window collapsed when you opened the hood and it was a light,

cheap, simple solution to the problem, but was not perfect as it tended to

form bubbles which could crack in very cold weather – I think – as

mine didn’t all the time I had it.

Maybe it was an acceptable solution if you accepted a 2 year

replacement life, after all we do that with tyres and exhausts. The

other main modification from the standard ‘Sport’ spec was to the

cooling and there I used the standard inlet duct on the front bodywork but

added the dotted rear ducted to improve the efficiency and added an

adjustable outlet flap. This

made the radiator ducting exactly as on the [DH] Mosquito and Hornet where

the drag was minimal due to heating the air and getting through from the

outlet jet – a bit like a ram-jet!

I was not after that effect but wanted the quick warm up when the

flap was closed. The position

was fixed by spring opening and a Bowden cable plus ball chain location on

the dash using wash and basin plug chain in a keyhole

socket [see illustration]. The

system worked a treat as the radiator was big enough for higher output

engines so was OK for hot traffic conditions but could be throttled down

for frosty mornings. I painted the headlight tunnels matt black to stop upward glare in the Hertfordshire winter fogs but the car was so low I found most fogs were non-existent below 3 feet so you could see quite clearly in what was a pea-souper in a normal car. I am sure I had a lot of comments on the line of “Mad sod, he’s driving far too fast!” when I was probably much more in my safe visual range than they were. You did have to watch ups and downs in the road as you were driving in a wide shallow tunnel. Before the paint I had tried a layer of grass and dirt in front of the the lights, when the covers were off, and once while parked, a policeman came up and lifted the grass out of the tunnel. He said, "ah, clever!" and placed it back. The

car was OK as a road car if you used your head and avoided things like

high kerbs into drives, Green Line bus exhausts, and idiots who used

knuckles to see how thin the Alumimium was on the wings.

If you have not worked it out the Green Line exhaust pipe was level

with a passenger’s ear and was very hot so in traffic you always had to

keep fore-and-aft space so you could move out of the way. It

was at the time of the Suez and petrol rationing so its low fuel

consumption was great. I got

well over 40 mpg and could get much more if I slipped out of gear and

coasted – it would run for miles with the low drag.

If you ask where was the odometer the answer was my log book and a

record of all trips plus fuel and my other events.

I learned that one from Mick Costin who had his diary on a shelf

with all the events on the car. When a problem cropped up Mike would say “just a minute

and I’ll get the details,” retire to his office and go through the

diary. He would re-appear

with a sheet of paper with all the relevant events listed in date order

– it was annoying how often the reasons were immediately obvious.

That discipline is why he was one of the best development engineers

in the game and is so much the reason for Cosworth’s success as

Keith’s design. Can’t

think of any more about XJH 875 so I will go and have my dinner off the

dining room furniture that was part of the spend when we sold XJH to the Chequered

Flag before I got married. From

what I hear XJH is still doing good service, like the sideboard,

table and chairs.

postscript – After concluding his volunteer design work on the Elite, Mac left Lotus to devote himself to aircraft design. His Eleven had been a gift from Lotus for his many hours of effort. Mac was therefore surprised when, several years later, he received a bill for the car and Chapman was ‘unavailable’ to intervene. He met Chapman again in 1969 and was offered the job of Chief Designer for Team Lotus. Mac declined the offer. (This information from Peter Ross’ book, LOTUS – The Early Years) Mac passed away on November 20, 2006. An honest man and a brilliant engineer, he will be fondly remembered. |